a little jump to the last equestrian century i.e., the1800s but first -

# my prayers are with wounded and hospitalized Prime Minister of Slovakia Robert Fico, who today was wounded in the attempted assassination in Slovakia. The shooter is an elderly poet and member of the Literary Club in Slovakia.*

***

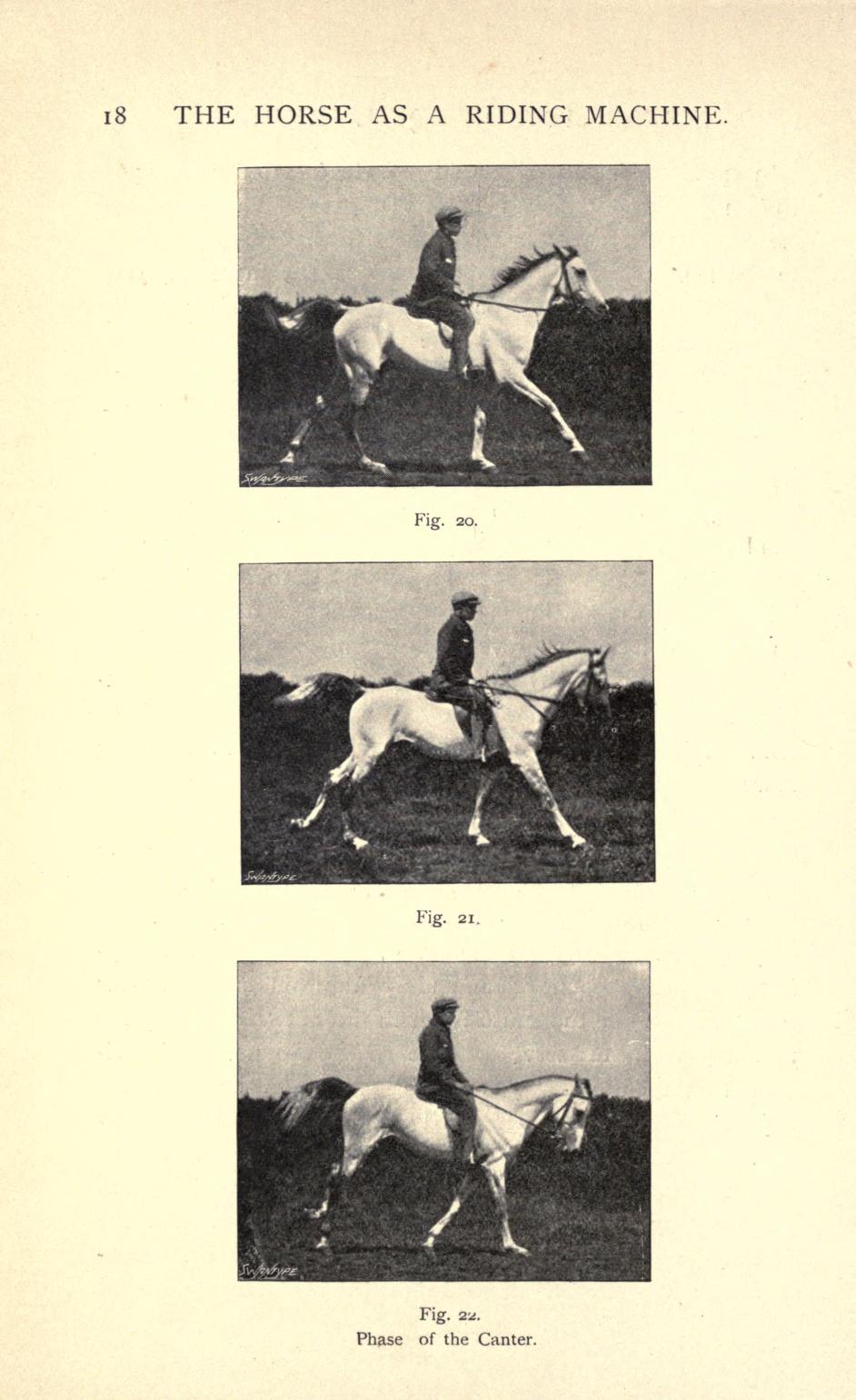

on military seat -

Cpt. H. Hayes et al., - from his book 'Riding and Hunting'

''The position without stirrups is described as follows in Cavalry Drill: "Each man should have his body balanced in the middle of the horse's back, head erect and square to the front, shoulders well thrown back, chest advanced, small of the back slightly bent forward The thigh should be stretched down from the hip, the flat of the thigh close to the horse's side, the knees a little bent, and the legs hanging down from the knee and near the horse's sides. The heels should be well stretched down, and the toes raised from the insteps, and as near the horse's sides as the heels. A plummet line from the front point of the shoulder should fall one inch behind the heel.

"While following these instructions, the man must, however, sit easily on his horse, without having his muscles unnaturally braced, and without stiffness. In order to get his toes and heels into a proper position, he should be taught to turn the flat part of the thigh from the hip towards the horse's side, and not merely to twist the foot inwards from the ankle or knee.

"This is the position halted, or at the walk; at the trot the body must be inclined a little backward, the whole figure pliant, and accompanying the movements of the horse. The elbows and lower limbs must be kept steady.

"The position with stirrups is nearly the same as without stirrups, the knee being a little more bent.

"A plummet line falling from the point of the knee should drop directly on the ball of the foot. The foot should be kept in its place by the play of the ankle and instep, the stirrup being under the ball of the foot. The lower edge of the bar is, as a general rule, to be from two and a half to three and a half fingers' breadths above the upper edge of the heel of the boot, when the man is sitting in the proper position.The Instructor must remember, however, that, though he should follow the general rules in fitting the stirrups, a great deal depends on whether the rider has a thin flat thigh or the reverse; a man with a thick thigh requires slightly shorter stirrups, otherwise, when the horse is in motion and the muscles are brought into play, he will not have a proper hold of the stirrup."Theodore Arayult Dodge in a few words on the riding seat:

''[...] then, it is quite impossible to say, as a whole, what seat is intrinsically the best, or what nation furnishes the best of riders. It appears to me that there is such a thing as a natural seat. Such a seat is clearly shown on the frieze of the Parthenon, and in a less artistic way may be seen among any horsemen riding without stirrups. Although Xenophon has been misunderstood in this particular, I feel convinced that his description calls for what I understand to be the natural seat. And the best military riders make the nearest approach to this position. By military seat I by no means intend to convey the idea of a straight leg, forked radish style. That is not the military seat proper. It is only in spite of such a seat, or in spite of the short stirrup of the East, and because they are always in the saddle, that the Mexican gaucho and the Arab of the desert both ride as magnificently as they do. The best military rider should and does, carry the leg as it naturally falls when sitting on his breech, not his crotch, on the bare back of a horse. The steeple-chaser, or crosscountry rider, for perfectly satisfactory reasons, has a much shorter stirrup. But on the road, he should, and generally does, come back more nearly to the natural length. The main advantage in the very long stirrup which obtains among so many peoples lies in the possibility of sitting close on a trot with greater ease, and of using the lasso or whip, or in having a free hand for their sundry sports or duties. And a high pommel and cantle are advantageous in helping the rider preserve his seat when he might be dragged — not thrown — from it in some of his peculiar experiences. But the perfectly straight leg always bears a suggestion of the parting advice of the groom to a Sunday rider just leaving the stable: "Look straight between his hears, sir, and keep your balance, and you can't come off." On the other hand, the advantages of an extremely short stirrup, such as prevails in the Orient, are very difficult to be understood at all.

Now the acquisition of this natural seat should be the first aim of every one who desires to become an expert rider, either in the manege or in riding to hounds.[...] But no man's seat can be too firm and strong. Bareback Riding.

Nor can light hands exist without a firm seat. There have been men of such abnormal muscular development that they distressed a horse by their grip. But this is unnecessary. Seat is not only a question of grip; balance comes in for a share of the credit.

You want to get down as close as possible to your horse. Some horses have what are called good saddle-backs (without having sway-backs, — a sign of weakness), which enable you to sit very close to them. Many very good horses have a high, straight back, which, however strong, makes your seat on them far less agreeable. But the best way for you, Tom, to acquire this natural seat, is to ride bareback a good deal, and afterwards to ride in a saddle without stirrups.

In the South all boys and girls learn to ride bareback; often without bridle, guiding their horses with a stick. Southern horses are treated with common sense and are usually very tractable. In all country districts, children who learn at all are apt to learn bareback. This develops the natural, or best, seat. And after riding in a saddle, it is well, as often as practicable, to revert for practice to the bareback, or the stirrupless seat in the saddle.

It of course attracts attention for a man thus to ride along the road; and no man, I ween aspires to be " the cynosure of neighboring eyes."

But it is easy at any time to get off on lanes and wood-roads, throw your leathers across the pommel, and practice this thing. And nothing will get you closer to your horse, or make you feel more at home upon him, than this very habit.

There is no better way to determine the proper length of your stirrups than to ride without them for a week, and then to put them in so that your feet, heels well down, will conveniently hold them.

(from Patroclus and Penelope, a chat in the saddle)Back to the military - Boniface in not a few words -

Cavalry horse and his pack :

The "tongs across the wall" seat is used largely by inexperienced riders and rarely by good ones. Its chief characteristic consists in keeping the knees stiff and straight and sticking the feet out to the front. Whenever the trot is taken up, it is necessary to materially alter the position of the legs, and in fact the entire position of the seat changes, owing to the difficulty of clinching with the thighs while keeping the legs stuck out stiffly. Riders who use this seat generally manage to ride horses possessing easy gaits, especially at the tiot. When using this seat, there is a tendency to lean back, thus boring the cantle of the saddle into the horse's back—in fact, it is next to impossible to ride at an increased gait and lean any other way in this seat. Among even good riders this seat is occasionally seen on- parade and at reviews, it being especially a "pose" seat. Some men in a troop learn this seat and they hold to it persistently, despite constant

efforts to teach them its inadaptability for cavalry riding. The seat, like the "fork" seat, though to a much greater extent, is not only uncomfortable to the rider when in line, but is very exasperating to the adjacent men, who, before the drill is over, generally manage to kick the man's legs and feet repeatedly, to break him of it. It may be taken for individual riding out of ranks, but the rider who attempts to use it in a cavalry troop will suffer many hard kicks and jolts and be the recipient of much hard swearing from his comrades.

The "hunting" seat, known also as the "long" or "chair" seat, is the typical cross-country seat when riding after hounds or in park-riding, and, in its place, is found to be very excellent, especially where jumping of four-barred country fences forms such a particular part of the riding. In this seat it is customary for the rider to hold the reins, together, with both hands. This is impossible in the "military" seat, where the trooper needs one hand for his weapons at all times. The stirrup used with the saddle usually employed by these riders is of steel and open. The hooded stirrup of the American cavalryman would be unwieldy and unnecessarily bulky on this saddle, while it has always been one of the parts of our military saddle especially held to; and for keeping the trooper's feet dry and shielded from the cold and wet of his long rides, as^well as for the safety to the rider, the hood is an important part of the military saddle, and affects the seat in a way, by defining the length of foot that can enter the stirrup, while with the open steel stirrup of the hunting saddle the foot usually goes in clear to the heel of the riding-boot. In the "hunting" seat the rider rests well down on his buttocks, the thigh is extended forward, generally at an angle somewhat more obtuse than that of the horse's shoulder; the leg from the knee to the ankle is loose and straight down, and if inclining in either direction, generally somewhat forward; the stirrup is very short, and the heel of the rider's fool; is considerable lower than his toe; the calf of the leg touches the sides of the horse, and it will be observed that this is the only one of the seats described in which this is the case; the calf does not press against the horse, but, owing to the entire seat and the short stirrup, it touches slightly, especially when jumping or galloping. In this respect the "hunting" seat resembles the Indian seat somewhat, except that in the Indian seat the leg from the knee down is drawn back and the heels touch the horse's flanks when the rider is, as the Indian generally is, riding without a saddle.

The "military" seat in the American Cavalry is the result of years and years of hard riding on the vast Western plains, and is well calculated to have the best effect on both horse and rider of any seat known for long rides, singly or in column, and for all drill purposes when security of seat, closeness of legs and feet, use of one hand, and comfort to the rider and his adjacent trooper comrades are considered. In this seat the rider sits evenly on his buttocks, inclining neither forward nor backward; the elbows are reasonably close to the body and somewhat drawn back; the reins are carried together

in the left hand, thus leaving the right hand free; the thigh is nearly parallel to the slope of the horse's shoulder; the leg from the knee down to the ankle is loose and straight down, and the heel is slightly lower than the toe, which is inserted in the hooded stirrup so that the ball of the foot rests on the stirrup tread; the rider's back is straight, head erect, and chin slightly drawn in without constraint. It is especially taught to keep the toes parallel to the sides of the horse, and thus the heels and spurs do not touch the animal's flanks except when the rider uses them intentionally. This latter position of the feet, it may be remarked, is difficult to acquire, and many men neglect it and apparently fail to appreciate its two excellent purposes—of keeping the spurs and heels out of the horse's flanks and keeping the flat of the thigh against the horse. The stirrup used with this seat is such that the rider, by standing up in them, can pass two or three fingers between his crotch and the saddle. The American cavalryman is disposed to use the long stirrup, and even in our correct regulation seat the length of the stirrup is much longer than that of any seat used in European cavalry, but experience has taught us that this length of stirrup is the most satisfactory one to use, especially on long marches.

The seats used in the various European cavalry services are more like that of the "hunting" seat, before described, than any other, and it is a general practice to use the short stirrup; the saddle used, being low and flat, with a covered seat of leather, enables the rider to assume this seat with much more comfort than can be done in the "McClellan" saddle; in fact, the correct "hunting" seat is almost an impossibility in the "McClellan" saddle, owing to the high cantle. The short stirrup is not used by any of those classes of riders who have bcome famous the world over for their hard rough-riding, excepting the Cossacks of Russia, who still adhere to it. However, as the Cossack rides in a saddle considerably above the back of his horse, this short stirrup is probably necessary. On the other hand, the use of a stirrup too long will, of necessity, subject the rider to much pounding, and though many men use it, they acknowledge that the pounding is harder; but, on the other hand, they claim that the entire seat is more secure, especially in the "fork" seat.

The best seat will be that in which balance, friction, and stirrups are combined in the right degree. To ride by balance alone would be very exhausting. To illustrate this, watch a recruit taking his first bare-backed lessons, before he has learned to use friction. Clinching the horse with the thighs, or "friction," as it is called, comes naturally and almost unconsciously as the result of training. At first requiring considerable effort, the rider gradually learns how to clinch without tiring himself, and eventually his clinching becomes very powerful without' tiring him. The writer remembers a Western rider with one wooden leg who declared that he had such power of clinching with his thighs on the horse's sides that he felt satisfied that*he could still ride should he lose the other leg. The leg that was gone had been amputated years before, from the knee down, and from what was seen of this man's riding, it is very likely that this rider could have done what he said. The early saddles possessed no stirrups, and the riders of those days must have been very perfect riders, using only balance and friction, judging from many authenticated accounts in military history; but gradually experience taught riders the world over that stirrups saved them much unnecessary fatigue by bearing the weight of the legs and feet, and also made the seat more secure in every way. The use of stirrups on all saddles, military or civilian, has now become universal, and their adjustment is a matter of great importance in riding and training, both as affects man and horse.

The proper length of stirrup will not be the same for any two men, as men differ in length of leg and in size too much. A man having a long, thin, flat leg will require a longer stirrup than a man having a short, fat, round leg, and no arbitrary length should be required for all troopers. A good method for securing the proper length is to hold the bottom of the stirrup-tread under the left arm with the right hand, snug in to the arm-pit, and then place the left hand, fingers extended, on the "D" ring (stirrup-loop) of the saddle, and then straightening out the left arm until the length of the stirrup thus measured corresponds with the length of the left arm placed as described. When the trooper is in the saddle, he should be able to place two fingers between his crotch and the saddle as he stands in his stirrups. All the men in the troop should be required to ride with a reasonably uniform length of stirrup; otherwise some of them will affectMa length of stirrup both unsightly to look at and absurd as regards the particular troopers. Both the Romans and the Greeks were ignorant of the use of stirrups, and either vaulted on their horses or used the back of a slave as a stepping-stone, or sometimes had recourse to a short ladder. The earliest time when it can be proved that the stirrup was in use was in the time of the Norman invasion of England. The incidents of this event were depicted upon the Bayeaux tapestry by the wife of William the Conqueror, and on this the stirrup was shown, according to the authority of Berenger, as a part of the trappings of the horse.

The position of the rider in the saddle is most important, because of its quick effect on the horse. If the rider leans back, his weight bores down upon the cantle, which in turn bores down upon the horse's back under the cantle, and the result; especially on the march, is a very sorebacked animal at least; the contrary fault of leaning forward causes the additional weight to bore into the horse's back under the pommel, in the region of the withers where several large, strong muscles and tendons are located, a free action of which is absolutely necessary at all gaits. The result of this leaning forward is not only a sore-backed horse, but probably it will also stiffen the animal up for weeks, especially if this fault exists during long marches. Leaning forward also makes the seat more insecure, and any stumbling or stopping of the horse at once throws the rider forward. The rider in the Cavalry should realize that the pommel and cantle on the "McClellan" military saddle are put there for the purpose of holding the pack up off the horse's back, and not as a means of support to the rider. The rider should sit in the middle of the saddle, erect, and support himself wholly by balance, friction, and stirrups. The pommel and cantle and reins should be used for what they are intended, and the seat of the rider should not depend upon them. The reins especially should be used only to guide the horse, and never as a support for the man on the horse's back. The continual sawing on the horse's mouth is a sure way of ruining the horse and tiring the rider, who not infrequently relieves his feelings by a sharp, savage tug at the reins.

The manner of riding known as "posting," whereby the rider rises at the trot, is much used in civil life and even in some European cavalry services; but, although permitted by our Cavalry Drill Regulations as a change from our close seat when in the field, is never so used, and has never found favor with American cavalry officers or troopers. Those who have thoroughly learned it speak highly of it as a seat both easy and simple, and not by any means the hard work to use that it is generally believed. Whether or not this "posting" is easy or hard on the horse has never been satisfactorily demonstrated, because no one ever has maintained it for long-distance riding. While perhaps good in park riding for pleasure, for short distances, in English saddles, this seat does not lend itself to long, hard rides, yet much praise is bestowed upon it by some European cavalry services.

The close seat is the typical American cavalry seat. There are many men, however, who never wholly acquire this close seat, but the mistake must not be made of thinking that the man who leaves the saddle more or less at the trot is a poor rider; on the contrary, many men leave the saddle somewhat at every trotting stride of the horse, and yet are excellent hard riders of record. The slight leaving of the saddle referred to, however, is very different from the awkward "bouncing" of the inexperienced rider, which is readily recognized wherever seen. Until the rider is himself proficient, he can do little but irritate the horse, and for this reason the recruit should be given a different horse every day, to enable the horse he rode the day before to recover from the awkward handling he has received. The recruit will learn more quickly to ride if given a different horse each day, although it will be hard upon him; but to ride well one must ride many different horses, hard ones and easy ones, and not confine himself to one particular animal. The gait of every horse is different from the gait of every other horse, and thus the rider learns the various forms of movement, and understands what is meant by a "hard trotter" and an "easy trotter"; until the rider has acquired skill and confidence and has had much experience in actual riding and handling of horses, he is not capable of training a horse, and should not be allowed to do so except under experienced troopers.''

the end of citation

Valete

ps

*The Fico's attempted assassination reminds me of the attempted assassination, stabbed with a knife, of then-presidential candidate in Brazil Jairo Bolsonaro, who wounded in the belly survived and lived to lead Brazil as president 2019-22. Slovakia like the rest of Europe is facing European Union parliament elections in June 2024.